How Computers Store Decimal Numbers

And Why It's Harder Than You Think

Most of the numbers we use in daily life are decimals. When you check your height, track your fuel consumption, or look at the euros sitting in your bank account, you’re dealing with quantities that almost never land on exact integers.

Computers don’t naturally like this. Early machines were designed to count things: apples, memory addresses, instructions — all integers. Decimals came later, often as a headache. Engineers quickly realized that there wasn’t a single “best” way to store non-integer numbers, so over the years they built several different numeric formats, each optimized for a specific world.

Scientists embraced doubles because they were fast and “good enough.” Banks insisted on decimals, because being off by a single cent can cost millions.

In this article, we’ll walk through these representations — doubles, decimals, Avro decimals, and more — to understand how computers store real-world numbers and why no single solution fits all domains.

Let’s start with the most common numeric type in computing: the double.

Doubles (IEEE-754 Floating-Point)

(The simplest — and surprisingly tricky — way computers store real numbers)

The double is the workhorse numerical type of modern computing. If you open almost any scientific library, graphics engine, or machine-learning framework, chances are you’re looking at doubles behind the scenes. They’re fast, predictable (mostly), and supported directly by hardware on every modern CPU.

A double is a type of floating-point number — the family of formats that represent real numbers using scientific notation in base-2. Whenever we talk about “floating-point” behavior or “floating-point noise,” we mean this representation.

How a Double Works: the 64-bit Layout

A double is defined by the IEEE-754 standard and occupies 64 bits1:

It stores numbers using binary scientific notation, the native language of the CPU:

This may look intimidating, but doubles were designed for speed. CPUs operate in base-2, so representing numbers in powers of two makes arithmetic extremely fast and efficient. Doubles also offer an enormous dynamic range.

The downside is that, because doubles use base-2, they cannot represent many base-10 decimals exactly. You can see this immediately in Python:

>>> 0.1 + 0.2

0.30000000000000004One of the most-upvoted answers in Stack Overflow history comes from a user surprised that 0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3. Developers around the world have had that same moment: the instant when they realize that computers don’t actually “understand” decimals.

This exact question has become a rite of passage in programming — a reminder that doubles do math in base-2, not base-10. The computer isn’t “making a mistake”; it’s simply doing binary arithmetic on numbers that cannot be represented precisely in binary.

Just like writing 1/3 in decimal produces 0.3333… with digits repeating forever, many everyday decimal numbers produce infinitely long expansions in binary. For example, the decimal value 0.1 has no finite binary expansion, so a double must round it to the nearest representable value.

But the reverse is also true: Fractions whose denominators are powers of two (e.g., 1/2, 1/4, 1/8) are represented exactly in IEEE-754, since they map cleanly to binary. These introduce no rounding error.

Doubles in Science and Engineering

In science and engineering, tiny rounding errors are rarely a problem because most physical equations are numerically stable: a small bit of noise only produces a small change in the result.

There are exceptions. Unstable systems or poorly designed algorithms can magnify tiny errors; the Patriot missile failure in 1991 is a well-known example where a small time-tracking error accumulated over hours with serious consequences.

But for the vast majority of scientific workloads, doubles are fast, predictable, and accurate enough for the physical world.

Doubles in Finance

Finance is different: money is exact. A rounding error doesn’t fade away — it accumulates. A one-cent drift repeated millions of times is not “noise”; it’s a real loss. This is why doubles, despite their speed, are entirely inappropriate for accounting or transaction systems.

That said, not every area of finance treats numbers this way. When I worked as a quant developer on a commodities trading desk, our pricing models — Monte Carlo simulations, PDE solvers — still relied on doubles. The reason is simple: these models behave much more like physical simulations than accounting systems. They’re inherently noisy and stochastic, and what matters most is speed. In that context, floating-point noise is insignificant compared to the randomness of the models.

Decimals (Numeric Type)

If doubles are the default numeric type for science, decimals are the default type for money. Unlike floating-point numbers, decimals store quantities in base-10 — the same way humans write numbers. This makes them slower, but it also makes them exact for values like 0.1, 1.25, or 19.99, which cannot be represented precisely in binary.

A decimal number is typically stored as an integer combined with a scale. For example, the value 10.8 might be represented internally as:

integer:

108scale:

1→ meaning “divide by 10¹”

This simple idea — store everything as whole numbers and remember where the decimal point should go — completely avoids the rounding surprises you get with doubles. That is why nearly every financial system, database, and accounting platform relies on decimal arithmetic.

But decimals come with trade-offs. They occupy more memory, because they store at least two numbers internally (the integer significand and the scale), and typical implementations use 16–32 bytes per value, compared to the 8 bytes required for IEEE-754 doubles. They are also much slower: unlike doubles, decimal arithmetic is not implemented in hardware and must be emulated in software. Despite these downsides, decimal types exist for one purpose and they do it well — represent base-10 quantities exactly.

In Python, using the Decimal type prevents the rounding errors we get with doubles:

>>> from decimal import Decimal

>>> Decimal(’0.1’) + Decimal(’0.2’)

Decimal(’0.3’)Decimals in the Wild: Avro Decimals

So far we’ve looked at decimals inside a single program. But real systems don’t live in one process — they stream data across Kafka, store it in data lakes, and exchange it between Java, Python, Spark, and Rust. For these systems to agree on what a decimal means, they need a serialization format, and one of the most widely used formats today is Avro.

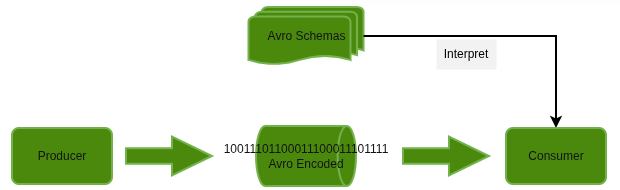

Avro separates two concerns:

a binary format for the actual bytes on the wire

and a schema that tells readers how to interpret those bytes

Avro doesn’t have a built-in decimal primitive. Instead, it defines decimal as a logical type layered on top of an integer. The schema specifies two values:

precision — the total number of digits the number may contain

scale — how many of those digits appear after the decimal point

On the wire, the decimal is stored simply as an integer. The reader reconstructs the real value by applying the scale:

Precision plays an important role here. Because Avro stores decimals as integers, it needs to know the maximum number of digits that will ever appear so it can allocate the right number of bytes and validate incoming values. If a writer sends a number that exceeds the declared precision, Avro will usually reject the message with a “decimal precision overflow” error. In other words, precision is not just metadata — it’s a contract.

This can feel restrictive. Once you pick a precision, you can’t exceed it without changing the schema, so teams typically choose a value that is safely larger than anything their system will ever encounter — often 18, 20, or even 30 digits. In one system we built recently, we spent a surprising amount of time trying to decide what that number should be. We needed a single precision that would safely accommodate any financial amount, across any currency, even under extreme conditions like hyperinflation. The goal was simple: pick a precision that would never overflow, not now and not twenty years from now — a reminder that this isn’t just a technical detail but a long-term design decision that quietly shapes the stability of an entire data pipeline.

Of course, a large precision isn’t free. Bigger precisions mean larger integers on the wire, which increases message size, slows serialization, and complicates schema evolution. This is why most systems choose a precision that is “large enough,” but not absurd.

The important part is the guarantee: a decimal written by Java, stored in Spark, and read in Python will have the exact same value. Avro decimals are simply the distributed-systems version of the same idea behind all decimal types — store the digits as an integer, remember where the decimal point goes, and let the schema carry the meaning.

Why Decimals Weren’t the Final Answer

Decimals fixed a major problem for finance — they made money exact. But they introduced a new one: performance. Every decimal operation happens in software, not hardware, and at scale this becomes painfully slow. Banks quickly realized that large pricing models and risk engines couldn’t run on decimals alone.

In other words, decimals closed one gap — but opened another. This is why new representations like UNUMs keep attracting attention: we’re still searching for a numeric type that is fast, compact, and exact.

The Search for Better Numbers: UNUMs

Even after decades of refinement, both doubles and decimals come with unavoidable trade-offs: doubles are fast but imprecise for many everyday values, while decimals are exact but slow and heavy. This has led researchers to ask whether we could design something better — a numeric format that is both fast and accurate, and that can express its own uncertainty.

That is the idea behind UNUMs, a family of alternative numeric formats proposed by John Gustafson. Unlike conventional floating-point numbers, a UNUM doesn’t just store a value; it also stores how precise that value is. In theory, this makes rounding errors explicit instead of hidden and allows computations to adapt their precision automatically.

It’s an attractive vision, but UNUMs remain mostly experimental. Their arithmetic is far more complex than IEEE-754, difficult to optimize, and incompatible with existing hardware and numerical libraries. The ecosystem cost of adopting them is simply too high.

And importantly, UNUMs do not solve the problems that matter in finance. Financial systems need exact base-10 quantities with predictable rounding rules; UNUMs, with their interval semantics and dynamic precision, are aimed at scientific workloads where uncertainty is natural. They improve on doubles, not on decimals.

For now, UNUMs stay in the research world — a compelling idea, but not yet a practical replacement for the numeric types we rely on today.

Conclusion

Computers have many ways to represent numbers, but each one reflects a different compromise. Doubles give us speed and convenience, but can’t express many everyday decimals exactly. Decimals fix that problem, but at the cost of performance and memory. Avro decimals add the guarantees needed in distributed systems, while UNUMs explore what numeric computing might look like if we ever redesigned it from scratch.

There is no single “best” numeric type — only the one that fits the world you’re trying to model. Scientists care about speed and stability; accountants care about exactness; distributed systems care about schemas and portability. For software engineers and architects, understanding these trade-offs is essential to designing systems that are robust, predictable, and aligned with the needs of the business.

IEEE-754 also defines a 32-bit format (often called float). Languages like C, C++, Java, Python (via NumPy), and Rust use both, with float giving about 7 decimal digits of precision and double about 15–17.